By Ryan Gowland

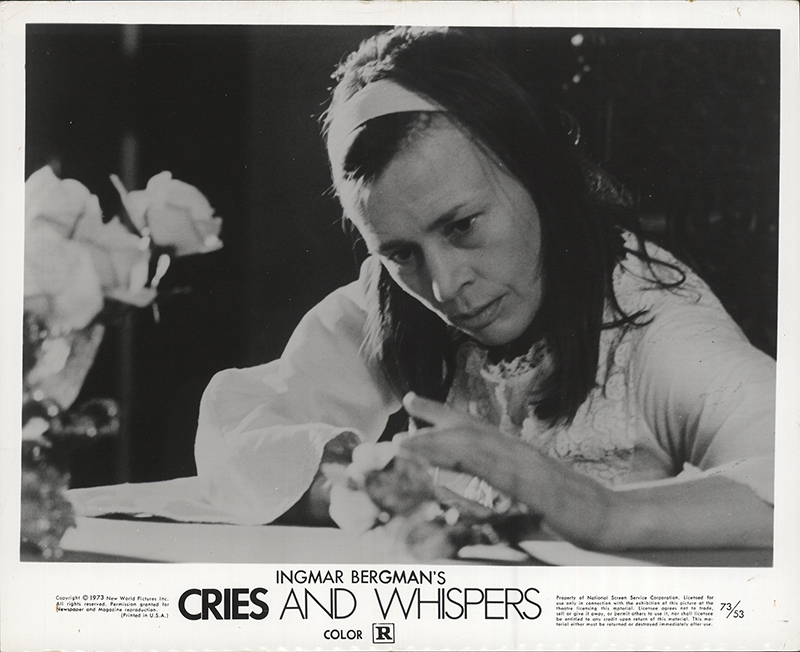

As we finish off our month of #JuneGloom selections, we saw a lot of responses from people that were unaware of New World’s association with Ingmar Bergman and CRIES AND WHISPERS (check out our episode here). It’s easy to see Roger Corman, the person most associated with New World Pictures even in the era after he sold the company, as a pioneer of exploitation and low-budget films. While many are quick to point out the array of talented and profoundly influential film-makers who got their start in his system, it seems too often lost the key role that New World Pictures played in reinvigorating foreign, arthouse film distribution. And CRIES AND WHISPERS is where it all began.

By 1972, New World Pictures was quickly establishing itself as a studio, finding instant success with a variety of exploitation and genre films such as the biker films ANGELS DIE HARD and BURY ME AN ANGEL, women-in-prison films such as THE BIG DOLL HOUSE and WOMEN IN CAGES, and the “nurses” cycle of films which began with 1970’s THE STUDENT NURSES. With a slate of films that included THE BIG BIRD CAGE, NIGHT CALL NURSES, and LADY FRANKENSTEIN, it was a big surprise that Corman would end the year by distributing his first art film, Ingmar Bergman’s CRIES AND WHISPERS.

The timing, for both parties, couldn’t have been better. Bergman was reeling from two disappointing films, especially 1971’s THE TOUCH, Bergman’s attempt to break into the mainstream after the ho-hum reception of 1970’s THE PASSION OF ANNA. “THE TOUCH was supposed to make a lot of money for its author,” Bergman admitted in his book Images. The Swedish director had worked alongside partner ABC Pictures in making his first English-language film with post-M*A*S*H star Elliot Gould, yet the film only managed mixed reviews and was a bomb at the box office. “I have probably resisted the temptation to make money more often than I have yielded to it, but there were times when I did yield completely and I have inevitably lived to regret it,” Bergman continued. “CRIES AND WHISPERS began to make its way forward during this depressing period.”

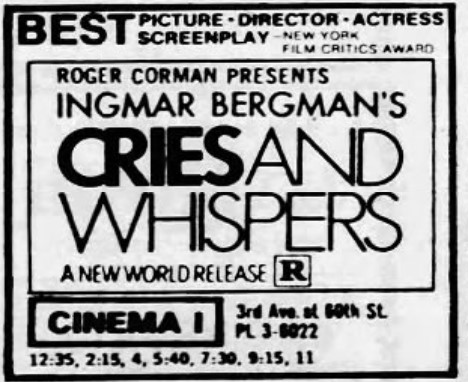

The appetite for more of his Bergman’s work – at least Stateside – was at an extreme low. As The San Francisco Examiner observed on January 28, 1973, less than a month after New World had released CRIES AND WHISPERS in New York City: “the American cinema industry had been examining the film since July [of 1972], but none of the experts seemed to think it a commercial proposition.”

None, that is, but Roger Corman.

As Corman explains in his autobiography How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, “Fairly early on, I began to worry the New World Pictures might become too closely associated with exploitation films. I had begun to feel we should move the company in an utterly different direction – the domestic release of art films from the finest directors in the world.”

Following that logic, Corman had reason to worry. Exploitation films had been the sum total of New World’s output. In fact, CRIES AND WHISPERS followed the release of THE WOMEN HUNT, a “most dangerous game” riff starring Pam Grier. So how was it that Roger Corman, the so-called King the B’s”, would come to release CRIES AND WHISPERS, the first of a string of foreign art films New World Pictures would distribute? Was Corman truly just looking to steer his company in a new direction?

Perhaps.

How exactly New World came to distribute CRIES AND WHISPERS seems to be a matter of debate. According to Christopher Koetting’s Mindwarp!: The Fantastic True Story of Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, New World sales manager Frank Moreno screened CRIES AND WHISPERS and bought it right away without notifying Corman. However, Corman’s story in his autobiography is that he had lunch with Bergman’s agent Paul Kohner and bought the film sight unseen. This is somewhat corroborated by Julie Corman, who said in An Oral History of New World Pictures Volume 2 that Kohner approached Roger about distributing the film.

Another version of the story arises in Beverly Gray’s biography Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. Gray notes that Moreno indeed discovered CRIES AND WHISPERS and quickly made a deal, which led Corman to boast about buying it sight unseen at a party until Kohner walked up, introduced himself and said to Corman: “‘You have not bought [the film] until you see it.'”

Whoever was the true arbiter of Corman’s pivot into the world of art films likely depends on which voice in this game of RASHOMON you want to follow, but what is inarguable is that New World released the movie when no one else would. To return to the question of why Corman would suddenly pivot from exploitation to the work of a foreign arthouse master, despite Corman’s lofty and ambitious claims in his book, Barbara Boyle can add some clarity.

“We were making summer product and drive-in product,” Corman’s former attorney and eventual COO of New World Pictures explained to Stephen Armstrong in An Oral History of New World Pictures Vol. 1. “I had one major problem. From October to May I couldn’t collect from the exhibitors. I couldn’t collect money, that is, because I had no product to give them.”

Enter Paul Kohner, who revealed to Boyle that the advance on the rights for CRIES AND WHISPERS would cost $75 thousand. “I thought to myself, ‘Roger loves Ingmar Bergman,'” Boyle explained. “Now the question is: ‘How do I get $75 thousand?’ Because Roger won’t put it up.”

The answer lied in Films, Inc., a Chicago-based, non-theatrical distribution company.

“They had acquired a bunch of our exploitation movies for shut-ins, hospitals, planes and all kinds of non-theatrical venues. I asked the head of Films, Inc. what he thought of CRIES AND WHISPERS and Bergman. He said, ‘We don’t really deal with foreign language films very much, but I love Bergman and I’d love to do it.'”

With the deal in place, Boyle had a way to collect from exhibitors because now she had product that would play in the fall. Corman was so pleased with the deal, he encouraged her to keep it going. “And that’s how I managed to acquire twenty-five of the greatest movies in the world in the ten years I was there,” said Boyle.

The acquisition was a huge success. Not only did it get excellent reviews, vaulting the status of New World Pictures in the process, it also was nominated for several Academy Awards, with Sven Nyqvist winning for Best Cinematography. Happiest of all, CRIES AND WHISPERS became one of the most successful of the early New World films, earning $2 million in gross rentals. Who else but Corman would put CRIES AND WHISPERS in drive-ins?

“Everyone thought it was insane,” Corman told Sight and Sound in 2020. “People thought Bergman would be outraged – a drive-in? When he heard about it, Bergman wrote to thank me for bringing his film to an audience he never anticipated having.”

The following year, New World released foreign pick-ups like THE HARDER THEY COME and FANTASTIC PLANET. The year after that, they released Federico Fellini’s AMARCORD. New World, as an art house film distributor, was off and running.